THE PICTS: SCOTLANDS INDIGENOUS

Originally by Mark Oliver; All That’s Interesting, edited by Kevin 'Buck' Buchanan for inclusion in Vol 51, Issue 2 of the Buchanan Banner, page 31

and augmented Matt Buchanan for web inclusion.

The Ancient Blue Wildmen who protected Scotland from the Roman Empire

A Roman perspective

Much of what we know about the Picts comes from the Romans, who praised the military prowess of these ancient Scots.

Their first written mention was by the Roman orator Eumenius in 297 CE, who mentioned them attacking Hadrian’s Wall.

Some 2,000 years ago, Scotland was home to a group of people known as the Picts. To the Romans who controlled much of Britain at the time, they were but mere savages, men who fought completely naked, armed with little more than a spear. But the Picts were fearsome warriors.

Every time the Roman Empire tried to move into their territory, the Picts successfully fought back. The Roman legions were the greatest military force the world had ever seen and the only people they couldn’t conquer were this wild clan.

Yet despite their formidable warrior culture, the Picts mysteriously vanished during the 10th century. The wild men the Romans could not conquer faded away and barely left behind a trace of their existence. Today, historians still struggle to piece together a glimpse into who the Picts were and what happened to their mighty culture.

“The Painted People”

Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues – A Pict woman drawn covered in flower tattoos

The Picts were so named by the Romans who observed and record them: “Pict” is believed to be a derivation of “The Painted,” or “Tattooed People,” which described the blue tattoos with which the Picts covered their bodies. But as was the case with many ancient peoples, the Picts did not refer to themselves as “Pict”.

Julius Caesar himself was fascinated by the culture. Upon meeting them in battle, he recorded that they “dye themselves with woad, which produces a blue color, and makes their appearance in battle more terrible. They wear long hair, and shave every part of the body save the head and the upper lip.”

According to other Roman sources, the only clothing the Picts wore were iron chains around their waists and throats. Iron was considered to them a sign of wealth and a material more valuable than gold. In addition, iron also served a practical use, the Picts could use these chains to carry swords, shields, and spears.

Their bodies were otherwise adorned head to toe with colored tattoos, designs, and drawings of animals. Indeed, these designs were so so intricate and beautiful that the Romans believed the reason the Picts didn’t wear clothes was to show them off.

The Romans Against The Picts

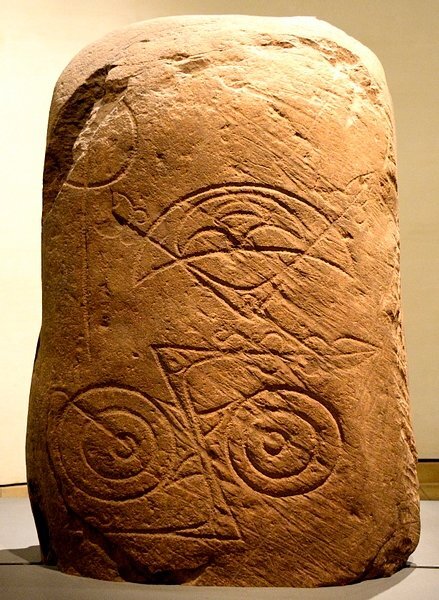

A Pictish stone tells of a battle scene, presumably the Battle of Nechtansmere of 685 AD

When the Roman Empire invaded Britain, they were accustomed to winning. They had conquered every powerful civilization they had yet come into contact with and destroyed any armed opposition with a flash of armor and steel that knew no equal. But they had never faced an enemy like the Picts.

The Romans expected another easy victory against the Picts, a primarily land-based people, going into their first battle. Indeed, the Picts retreated nearly as soon as they’d started fighting, and the Romans declared: “Our troops proved their superiority.”

But the victory proved to be an illusion. While the Romans were setting up camp, the Picts returned pouring out of the woods and seemingly out of thin air. They caught the Romans completely unaware and massacred them.

An Undefeatable Opponent

A Pictish rider drinking on horseback.

Time and time again, the Picts would lure the Romans into a false sense of security before striking when their guard was down. For instance, they would often charge the Romans on horseback and immediately retreat, luring the Roman cavalry away from their infantry. Then, a second squad of Picts would leap out of the woods and slaughter any Romans that had been foolish enough to give chase.

“Our infantry,” Julius Caesar wrote, “were but poorly fitted for an enemy of this kind.” Indeed, when the Romans took over a Pict village, the clans would move on to another one and prepare to strike back. Much like Napoleon could not pin down the enemy and force them to fight on his terms during his invasion of Russia, the Picts continuously frustrated the seemingly-superior Roman forces by their refusal to fight in the Roman way.

The Picts were faster, knew the land better, and had they more to fight for. By Roman counts, some 10,000 Picts died fighting against their forces — but Scotland never fell to them.

In 122 CE the emperor Hadrian ordered the construction of his famous wall which ran for 73 miles (120 km), sometimes at a height of 15 feet, from coast to coast. In 142 CE, the Antonine Wall was constructed further north under the reign of Antoninus Pius.

The walls served as psychological as well as physical barriers. However, these walls did not discourage Pictish raids.

When the Romans left Britain in 410 CE, the Picts still lived in the regions north of the wall as they always had. Whatever effect the Roman presence may have had on them is unknown, but the carvings the Picts left on their standing stones show no major differences in lifestyle from before the arrival of Rome to after the departure of the legions.

This story, though, is one told by an invading force. It’s a Roman version of the Picts, which is likely far from the whole truth.

A depiction of a Pict warrior, painted as described in Roman history.

Historically speaking…

The origins of the Picts are hotly are disputed: one theory claims they were formed of tribes who predated the arrival of the Celts in Britain, but other analysts suggest that they may have been a branch of the Celts. The coalescence of the tribes into the Picts may well have been a reaction to the Roman occupation of Britain. But it is generally accepted that the Picts were not a race of one people, but several tribes that united.

The Picts are often described as the descendants of the indigenous Iron Age people of northern Scotland.

It’s hard to say what life among the Picts was really like as almost no Pict writing has survived to this day. The only hints we have come from a scattered handful of relics uncovered in British archaeological digs.

Language is equally controversial, as there’s no agreement on whether they spoke a variant of Celtic or something older.

What we’ve found, though, bears little resemblance to the Roman version of the story. The Picts, historians believe, weren’t a particularly warlike people. With the exception of a few cattle raids between neighboring tribes, they lived in relative peace only taking up arms when the Romans forced them to defend their homes.

There is little proof even that they really fought naked. Most of what archaeologists have discovered about the Picts comes from the 5th century or later, but by then, at least, the culture had taken to using linen, wool, and silk. They drew themselves dressed in tunics and coats in pictures.

Interestingly enough, the Picts seem to have been farmers and were a peaceful people who focused their faith on nature. They believed a goddess had walked through their lands and that every place where her foot had landed was sacred. Their fierce commitment to their ancestral land is likely what motivated them to become fearsome protectors of it and a dangerous enemy to the Romans.

Christianization and Dissappearance

William Hole – Saint Columba converting the Picts to Christianity.

In the end, it wasn’t the drums of war that toppled the Picts: it was the cross. In 397 AD, Christian missionaries started moving into the Picts’ territory and spread the message of Jesus Christ. One of the most successful individuals in converting the Picts was Saint Columba, who famously won over the clans by banishing a monster they thought dwelled in the River Ness – a story that’s believed to be the basis for the legend of the Loch Ness Monster.

By this point, Pictish culture began to change. More and more, they became influenced by their Gaelic neighbors and started to imitate their language and beliefs.

British Isles, about 802. Showing Pictland, Dalriada, Strathclyde and Northumbria; where Scotland stands today

The last Pictish kings died in 843 AD — killed, depending on who you believe, by either the Vikings of the Scots. After this, the King of the Scots, Cinaed Mac Alpin or Kenneth MacAlpin, crowned himself as their ruler and formally united the Picts with the Scots.

At the same time, Scotland was threatened by ongoing Viking raids. The remaining Picts had no choice but to fight side-by-side with the Scots to defend their ancestral land. By the 10th century, their Kingdom was wholly transformed into the Kingdom of Alba, and their own language was replaced by Gaelic. The last traces of a distinct Pict culture were lost.

Fortunately, small hints about who these people were continue to be uncovered. A handprint on a stone here, a symbol on a wall there; every new artifact uncovers a little more of what life was like for “Europe’s Lost People,” the ancient tribe that once struck fear into the heart of the mighty Roman legion.

“They were the most extraordinary artists. They could draw a wolf, a salmon, an eagle on a piece of stone with a single line and produce a beautiful naturalistic drawing. Nothing as good as this is found between Portmahomack and Rome. Even the Anglo-Saxons didn’t do stone-carving, as well as the Picts, did. Not until the post-Renaissance were people able to get across the character of animals just like that.”

More than 250 stones with Pictish symbols survived and these can give us a better understanding of the Picts. Some Pictish stones have written inscriptions. Pictish letters - called 'ogam' - had no curves, so they were well suited for carving on stone.

Earliest records suggest that early Celtic/Pictish tribal blood very much runs through Buchanan veins! We know that Buchanan ancestors have lived here since records actually began. The ownership of the small silver Leny sword circa 971, indicates they were long established as Chiefs for well over 1000 years. |

Alba

Alba is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is also used to refer to the polity of Picts and Scots united in the ninth century as the Kingdom of Alba, until it developed into the Kingdom of Scotland of the late middle ages following the absorption of Strathclyde and English-speaking Lothian in the 12th century.