The Ragman Roll

In 1291, There were a number of claimants to the Scottish throne and King Edward I of England "volunteered" to hear their case and decide who had the most valid claim.

Those involved met Edward at Norham on Tweed in 1291.

Edward insisted on all the nobles signing an oath of loyalty to him.

Some declined but many signed what was the first (and smaller) of the "Ragman Rolls"

When Balliol began to resist the demands of Edward in 1296, the English King over-ran Berwick-upon-Tweed and defeated the Scots at the Battle of Dunbar. He then marched across Scotland as far as the Moray Firth, capturing castles and removing such precious items as the Stone of Destiny, the Scottish crown and huge archives of Scotland's national records.

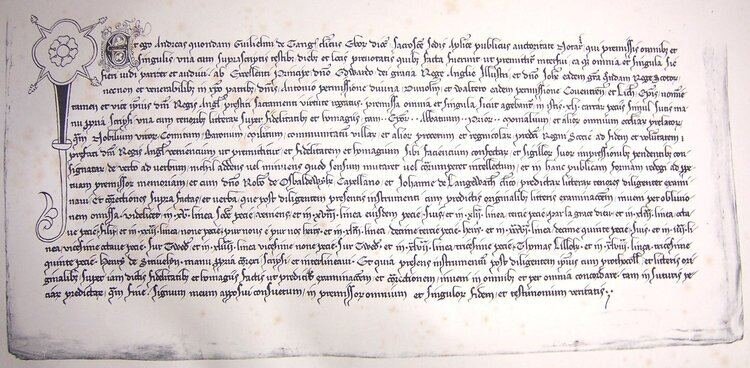

On 28 August, 1296, Edward held a "parliament" at Berwick. All the prominent Scottish landowners, churchmen and burgesses were summoned to swear allegiance to Edward and sign the parchments and affix their seals, many of which had ribbons attached.

Prominent people as :

• Robert Bruce, 6th Lord of Annandale,

• his son, the 2nd Earl of Carrick and

• William Wallace's uncle, Sir Reginald de Crauford

all of whom signed in 1291, did not sign in 1296.

The roll of 1296 provides the first extant mention of the arms of a Buchanan. Malcolm de Bougheannan with the charge being recorded as a fox or wolves head, with the inscription S’ Malcolm d Nvadeoc.

REFERENCE see “Attached by strings are… #3597”

In total, 2,000 signatures were inscribed, making it a most valuable document for future researchers.

It is suggested that the term "Ragman Rolls" derived from the ribbons attached to the seals on the parchments. The rolls are still preserved in the Scottish record office.

Edward I of England (AKA Edward Longshanks)

Edward I was considered to be the English Justinian, who was known as Edward Longshanks because of his – for the period – extraordinary height of 6’2”.

By the standards of his time, Edward was a true Christian King – “a just and chivalrous paladin of Christendom.” It was in pursuit of justice for all and his royal rights for himself that Edward set about its reform.

On Sunday August 19th 1274 he was crowned at Westminster, swearing to “confirm and observe the laws of ancient times granted by just and devout kings unto the English nation” and to minister equity and justice. The next day he received the homage of the magnates of the realm including the King of the Scots. The coronation feast went on for fifteen days, but long before the feasting was over Edward had left.

He progressed through the more populous parts of England, and with him went his court of King’s Bench, with its judges, pleaders, attorneys, to hear local pleas and petitions. Wherever he stopped, the pleas of his court were proclaimed. Everywhere he seems to have been received with enthusiasm and to have been greatly touched by his peoples welcome. He was moved, too, by their complaints. During his absence from England at the crusades, there had been much misgovernment. In a medieval State without a police force, and with little administrative service, where most villages were several days journey from the capital, and in winter completely cut off, corruption was inevitable.

It was one thing for the king and his council to issue commands and ordinances, another to get them obeyed, even by his own officials. The most he could offer was remedial justice for abuses committed, and there had been many.

Sheriffs and their officers had taken bribes, been extortionate, refused writs or sold them at inordinate prices. The country had settled somewhat, after the baronial strife under Simon de Montfort, but there existed widespread resentment between lord and tenant, neighbour and neighbour – a state of affairs which invited disorder in an age when men were swift to anger and violence. Everyone seemed to be trying to enlarge his rights at someone else’s expense and to take advantage of the complexities of the law to do so. There was so much uncertainty about the law, and so many ways in which a man might employ unscrupulous means to obtain his ends that something approaching legal civil war existed. Soon after the start of his progress, Edward appointed commissioners to enquire into the “abuses and usurpations, particularly of royal rights and revenue, that had occurred during his absence.”

The Ragman Roll’s benefits to Heraldry

The Ragman Quest was and is still today considered an administrative miracle, was carried out in the depths of winter and completed in just over four months. In the Roll, we can follow the commissioners of Edward I as they travelled in groups of two or three through the country, taking down the testimony of jurors and others.

Throughout the winter they toured the shires, taking evidence on oath from juries of every borough and liberty. Their returns, made on slips of parchment from the seals of the testifying jurymen which hung from them, became known as the “ragman” rolls.

They provided a wealth of information about the malpractices of landowners, sheriffs and bailiffs, and about encroachments on Crown rights. In no less than nineteen counties Edward found it necessary to dismiss the sheriff for extortion or abuse of the law. Charges were bought against the bailiffs and bedels who lived on the fees of jurisdiction, and far from any central control, were under heavy temptation to use law to feather their nests. With their pompous, bullying ways, many bailiffs were real tyrants, like the one who “caused all the free tenants of a village, to the number of eighty or more, to come before the kings justices to make recognition in a certain assize and, when they were come, said to them, ‘Now you know what the bailiffs of the lord king can do,’ and that was all he did.” Having learnt through his inquest what was wrong with his realm, Edward had resolved on great changes. For these he needed his subjects witness and approval. In the provisions of Oxford in 1258 the barons had laid it down that parliament should “have the power of advising the king in good faith concerning the government of his kingdom – in order to amend and redress everything that they considered in need of amendment and redress.” The attempt by de Montfort to make such authority independent of the Crown had failed, but in the Statute of Marlborough of 1267 Edward in his father’s name had legalized the baronial reforms of the past decade by a solemn public act of the Crown, issued in parliament under the great seal and enrolled in writing as a permanent national record. Henceforward such statutes, as they became called, were cited in pleadings in the royal courts, and like Magna Carta they became part of the continuing life of the nation. In 1290 an important matter concerning Scotland arose.

And why, prior to 1291, were there many claimants to the Scottish throne?

Three years earlier, after crossing the Forth on a stormy evening, Alexander III of Scotland had ridden over a cliff while galloping through the night to join his queen at Kinghorn. Since all his children had died before him, including his daughter the Queen of Norway, his death at 44 left Scotland with no direct heir but the infant child, the Maid of Norway.

The death of Alexander caused great concern amongst the more responsible Scottish leaders who, two years earlier had sworn to accept the infant Maid of Norway as heir to the throne should Alexander die without offspring. In their dilemma they turned to Edward, from whose sister, first wife of Alexander, the Maid of Norway was descended. Soon after Alexander’s death two friars arrived in London with a message from the guardians of Scotland to suggest a possible marriage between their child queen and the five year-old son and heir of the English king, Prince Edward.

Four Scottish regents – Robert Bruce earl of Carrick, John Comyn of Badenoch, and the bishops of St. Andrew and Glasgow; together with representatives from King Eric of Norway, had signed a treaty under which the infant maid was to be sent to Britain within the next year, Edward agreeing to deliver her free to Scotland as soon as the latter was sufficiently pacified to receive her, and the Scots to accept her as their queen and not to marry her without his consent.

In July 1290 a treaty sealed at Brigham by commissioners representing the two countries provided amongst other matters, that Scotland should remain “free and intact of any subjection to the King of England,” and that its “rights, laws, liberties, and customs” should be “wholly and inviolably reserved for all time,” and that it should remain “separate and divided from the kingdom of England by its right boundaries and marches – free in its self and without subjection.” Further, that no parliament was to be held outside Scotland on any matter that concerned it, and no taxes should be exacted from its people except to meet the common expenses of the crown. It was agreed, too, that until the pair could marry and take oaths to preserve the customs of the realm, Edward should hold the Scottish royal castles to ensure peace and order.

On returning to England Edward confirmed the treaty on August 28th at Northampton.

He now began to prepare for a knightly Christian adventure which was to be the crowning act of his life. It had been agreed with the pope that new crusade was to be launched in the summer of 1293, being the 57th year of the king’s life. A few days after Edward met his parliament to discuss the coming crusade he received a disturbing letter. It was written by William Fraser bishop of St. Andrews, and it reported a rumour that after a stormy voyage across the North Sea the Maid had died in the Orkneys, What was more disturbing was that the Bruces and other Scottish nobles with rival claims to the throne were in arms and gathering forces. Before confirmation of the situation in Scotland could arrive, news even more dire reached Edward, His queen had been taken ill at Harbey in Nottinghamshire. On November 28th she died in his arms. “My harp is turned to mourning” he wrote, “In life I loved her dearly, nor can I cease to love her in death.”

She had been an inseperable companion for thirtysix years and had borne him thirteen children, of whom seven had died before her. For the rest of Edwards life nothing ever went wholly right for him. From Amesbury where he went to visit his dying mother Edward asked for extracts from the monastic chronicles to prove his right to Scotland’s overlordship. Scotlands last two kings, both of whom had married English princesses, had done homage for their English estates. In accepting such limited fealty Edward had expressly reserved the right to call for a wider, and there had been occassions when it was rendered. William the Lion, and Alexander II both paid tribute, the first after his capture, doing homage to Henry II for his Scottish fief and crown – a vassalage renounced by Richard Coeur de Lion in return for money for a crusade. And before the union of the Scottish Kingdoms two centuries earlier homage of a kind had been rendered to England’s Anglo-Saxon rulers by the princes of northern Britain. The difficulty was that, though such precedents might satisfy an English Judge, they were unlikely to carry conviction to the Scots. Armed with these records of hereditary right Edward summoned the claimants to the vacant Scottish throne to meet him at Norham in Northumberland. At the beginning of May 1291 he meet the representatives of Scotland, announcing that out of pity for their plight he had come “as the superior and lord paramount of the kingdom of Scotland” to do his lieges justice. Yet he could only do so under the terms of feudal law. Before the king’s court could adjudicate, the vacant fief must be surrendered and his right as overlord acknowledged. The Scottish representatives asked if they might consult those who had sent them. Their reply on “behalf of the community of the good people of Scotland” argued that whilst the did not doubt Edwards sincerity, they knew of no right to his overlordship and could not bind their future sovereign to it. Edward offered a three week period for them to consider the proposition. As the only alternative to his adjudication was civil war, none of the claimants to the scottish throne in the end refused what he asked. At the beginning of June they all swore to submit to his judgement and abide by his decision. Having secured his point Edward demanded the surrender of the Scottish royal castles while the claims were determined. Edward procalimed his peace, promising to govern Scotland according to its ancient laws and customs. He then set out to tour the country. During July he visited Edinburgh, Stirling, Dunfermline, St. Andrew and Perth, installing constables in twenty three castles and exacting as many oaths of fealty as possible. At Berwick at the beginning of September twenty four English judges or auditors, and eighty Scottish accessors to advise on Scottish law commenced the examinations of the claims. Each competitor including the King of Norway and the Count of Holland appeared before Edward and his auditors in person, or by attorney, and traced his descent from the ancestor from whom he claimed. After ten days the evidence was placed in a sealed bag and the court adjourned to enable the Scottish assessors to prepare their replies.

When the hearings resumed in October all the claimants had been eliminated save three descended from William the Lion’s younger brother, David earl of Huntingdon – a tenant-in-chief of Edwards great grandfather, Henry II. The nearest in blood and the most favoured by his fellow magnates was as on of the second daughter, the 81 year old Robert Bruce. An Anglo-Scottish noble who has served Edwards father as chief justice of the King’s Bench and who before the birth of the last Scottish king was acknowledged as heir-presumptive. But under the rules of primogeniture that were coming to be accepted by the more settled kingdoms of the west, a better claim was John Balliol’s whose father had married the daughter of Huntingdon’s eldest daughter. He too was an English as well as a Scottish magnate; his father, lord of Barnard Castle, had fought by Edwards side at Lewes and had founded an Oxford college for poor students from the north. After long consideration the eighty Scottish auditors – half chosen by Bruce and half by Balliol – failed to agree, the decision devolved on Edwards judges who followed the accepted English usage that issue of the eldest line must be exhausted before succession could pass to a younger. On November 17th. 1292 after six weeks of hearing, the Scottish throne was awarded to John Balliol. The magnates did homage to their new king and later did homage to Edward as supreme sovereign lord. The unsuccessful runner-up old Bruce, avoided acknowledging his rivals claim by relinquishing his rights to his son, the earl of Carrick, who with the same object, made over his Scottish estates to his son, Robert Bruce, a minor, subsequently sailing to Norway to marry his daughter to the widowed King Eric – father of the little princes whose death had caused all the trouble.

Balliol was installed at Scone on St. Andrews Day on the historic Stone of Destiny. He was a quiet, unassertive man, little fitted to serve as a buffer between a turbulent native nobility and a suzerain as zealous for formal law and order as Edward. Trouble began almost immediately. A Berwick merchant appealed to the English courts against a decision of the Scottish Justiciars. Edward ordered the record to be brought before the King’s Bench at Newcastle. Balliol reminded him of his undertaking made at Brigham, that no Scottish subject should be made to plea in any court outside Scotland. Edward replied that he was not bound by a marriage treaty that had not been carried out. Further, he extracted a homage from Balliol and made him sign a document releasing him from every “article, concession or promise” made at Brigham. It was a major political blunder. Once Balliol had renounced his kingdoms rights to the conditions secured at Brigham, he was lost. During the next two years he was repeatedly called to answer appeals to his overlord’s court at Westminster as though Scotland were an English barony. The most humiliating of all was an appeal by the son of a former Earl of Fife against a judicial decision of the Scottish council or parliament. Balliol made a stand at last and refused either to answer at Westminster or to ask for an adjournment, on the grounds that, as Scotland’s king, he could do neither, without the consent of “the good men of his realm”, he was adjudged to be in contempt of his overlord’s court and ordered to hand over three of his strongest castles. Whereupon he stood back, once more, and acknowledged himself Edward’s man. His subjects called him “The empty jacket”. Faced by their resentment and the English kings demands, he was between the devil and the deep sea. A contemporary wrote of him “A simple creature, he opened not his mouth, fearing the frenzied wildness of that people lest they should starve him or shut him up in prison. So he dwelt with them a year as a lamb among wolves.” Edwards problems continued in France were his cousin Philip the Fair had promised to, respect the ties of family affection between the royal houses of England and France, had by using the same legal processes as Edward laid claim to fiefs by “juristic finesse and judicial confiscation,” and despite Edwards effort to have the many disputes adjudicated in an English court, tried by an Anglo-French commission, or referred to papal arbitration

Philip rejected all his offers and insisted on his rights as overlord to be sole judge. Edward of course was a king with an overlord – for his fiefs in France. Edward did all he could to compose the matter, and made a formal surrender of Gascony in accordance with feudal law, and received a private undertaking from Philip that it would be returned as soon as the matters outstanding were settled. Edward authorised the lieutenant of Gascony to deliver possession of its castles to the constable of France, upon which a French army entered the duchy and occupied Bordeaux. After waiting six weeks Edmund asked when Philip’s part of the bargain was to be fulfilled, he was told that his overlord would restore nothing. On May 15th 1294, it was announced in the parlement of Paris that the Duke of Aquitane had forfeited his fief by his contempt. Edward had been, under the outward forms of law, hoist with his own petard, and been tricked out of his French hereditary dominions. With the two strongest countries in Christendom at loggerheads, a crusade was now out of the question.Edward placed an embargo on French shipping, closed his ports and ordered his vassal, the Scottish king to do the same. Preparations for an invasion of France were now set in train which necessitated a heavy fiscal drain on English, Welsh, and Scottish tax payers. He could not finance the the recovery of the duchy from his own revenue, however much credit he received from the Italian bankers, and in the last resort the war had to be paid for by feudal tenants, landowners, and traders of Britain and for this he needed their consent. It was not easy to obtain for the country considered the defence or recovery of the sovereign’s French fief as none of their business. Though he had no right to tax them without their consent, they dared not refuse. So great was the terror he aroused in them that the Dean of St. Paul’s dropped dead at his feet. The Welsh saw the confusion as an opportunity to rid themselves of a hated subordination and Welsh levies had, under the leader ship of a scion of their old princely house, swept down on Caernarvon Castle. Other parts of Wales under different leaders were also in rebellion. Edward reacted with his usual terrifying speed. Abandoning all other matters he prepared for a winter campaign, and by the end of a month had assembled an army of fighting Earls. By Christmas he was in his castle at Conway trapped there by a Welsh detachment, short of food and wine. It was a grim fortnight, the Welsh besieged tha castle and all round were flooded fields and rivers, and the bitter winter cold. Befor January was out the castle had been relieved. Shortly after during a night attack the Welsh were surprised by the Earl of Warwick and the force annihilated. After this the war turned against the Welsh and by the summer of 1295 Edward was in control. He had lost a year. Scarcely had he resumed his preparations for invading France than he was faced with a new threat to his rear. The Scottish king had three years earlier been summoned to join the feudal hosts at Portsmouth with is steward, eight earls, and twelve barons. He had failed to appear and in the summer of 1295, had secretly received an embassy from Paris to discuss a marriage between his eldest son and the French king’s niece. On October 22nd 1295, a treaty of alliance was concluded between France and Scotland intended to force Edward to abandon his “perverse and hostile incursions into France.” It was agreed that the King of Scots should “begin and continue war” against him with all his power. If France were attacked Balliol was to invade England, and in return France would distract the common enemy in other parts. Balliol now seized the estates of all Scottish noble with land in England including those of his rivals, the Bruces. Edward was not a man to let treason – as he deemed it – pass unpunished. He found it much easier to raise funds for a Scottish campaign than a French one, and was voted by an English parliament the funds required with a promise of more to come if needed. By march 1296 he was ready to strike

During this first period of assembly, the army was joined at Wark by a contingent of Anglo-Scottish nobles, led by the earls of Angus and Dunbar and the two Bruces. All of them did homage and fealty for their Scottish lands. Balliol began with a raid across the border, and in response on March 28th, Edward crossed the Tweed at Coldstream and called upon Berwick to surrender. The burghers of Berwick mocked him and when the next day the city of less than 2000 souls was sacked in accordance with the usual practice when a town refused to surrender. There was a massacre in which, according to Scottish records, women and children as well as men suffered. English chroniclers deny this. Edward remained at Berwick for a month rebuilding its walls, and then, the Scots played into his hands. The countess of Dunbar changed sides and surrendered to family castle, on the road to Edinburgh, to the Scottish army. An English contingent was sent to recover it, and the main Scottish army marched to its relief. The ensuing battle at Spottsmuir, met with complete disaster. John Comyn the Scottish commander, was taken prisoner together with three other Earls and more than a hundred of Balliol’s chief adherents. On July 2nd Balliol submitted. The unhappy man apologised for the French alliance – caused “through evil counsel and our own simplicity” – accepted Edward’s terms and acknowledged himself in mercy. A week later he abdicated at Brechin Castle and sent to England. Edward continued his march. By the end of the month he had traversed Scotland further north than any other ruler since the Romans. He then struck east and retraced his steps reaching Berwick again on August 22nd. On the way he took the Stone of Destiny from Scone abbey and the Black Rood of St. Margaret from Edinburgh, and sent them, with the Scottish regalia and national archives, to Westminster. He had conquered Scotland and searched it through in twenty-one weeks. He held a parliament at Berwick and received the homage of two thousand Scottish landowners – the entire “franchise” of the land.” The king restored all estates in return for sealed submission, copies of which were sent to Westminster on thirty five parchment skins known as the “Scottish Ragman Roll.” “Now,” wrote a ballad-maker, “are the two waters come into one realm made of two kingdoms. Now are the islanders all brought together and Alban is rejoined to its regalities of which Edward is lord.. There is no longer any king except King Edward. – Arthur himself never had it so fully.” Shortly after this period Wallace began his rebellion. But that’s another story.

This article is taken from the book by Arthur Bryant – The Story of England – The Age of Chivalry – and has been suitable shortened.

Claude Askel Buchanan, FSA Scot

Herald at Arms Emeritus